![]()

|

Demetri Kantarelis dkantar@assumption.edu, an Associate Professor of Economics, Department of Economics and Global Studies at Assumption College, completed the research for this paper during the 1997-98 academic year while the author was visiting the Department of Future Conflict Studies at the Air War College/Air University, Maxwell Air Force Base, Montgomery, Alabama. |

There was a great deal of debate on whether or not the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) should continue existing after the 1991 breakup of the Soviet Union and the earlier dissolution of the Warsaw Pact. From 1991 to 1995, the NATO Alliance was perceived by some as missionless and less able to influence events as it became leaner and weaker.

After 1991 the immediate NATO responses to the changed circumstances it faced were: (1) a reduction in the number of commands from three to two, (2) the replacement of large standing forces by multinational rapid reaction forces, and (3) a reduction in the headquarters staff by more than one third, resulting in a staff composition with greater European presence and less U.S. personnel than before. But NATO's destiny was to be rewritten. By itself alone, the Bosnia crisis proved wrong those who declared the Alliance missionless. The Dayton Accords and NATO's effective involvement in the Bosnia conflict helped remind us of the true mission of the Alliance, a mission that was there all along. As the 1997 NDU/INSS Strategic Assessment states:

"The 1949 Washington Treaty establishing NATO signifies common principles of democracy, liberty, and the rule of law. Neither the ideological threat of communism nor the Soviet Union are mentioned. The concept of Europe is not defined in the Treaty as West or East. NATO's success during its first forty years should be judged as much on what it helped create - a prosperous West Europe, whole and free - as what it stopped: an expansionist and hostile ideology. Whatever steps NATO now takes throughout the rest of Europe to promote wider peace and security are in consonance with the original Treaty." [1]

Although the above quotation reminds us what NATO's real mission is, the end of the cold war brought with it many new and more difficult challenges. These challenges are potentially less lethal, but are still very dangerous and extremely complex. Logically, the Alliance has to adapt and evolve and, as it does so, remain focused on its mission. We have to keep studying its dynamic threat environments and how we can best prepare to deal with them.

Discussed in the remainder of this paper are NATO's mission (Section II); threats to it (Section III); some principles of alliance theory that may be useful in guiding NATO in its new path of dynamic evolution (Section IV); and a conclusion (Section V).

II. NATO's MissionNATO's mission, as one may redefine it today, is to protect the interdependent economies of West/Central Europe and North America from internal, peripheral, and external peace-disturbing crises. Undoubtedly, this is a mission in consonance with the original 1948 treaty.

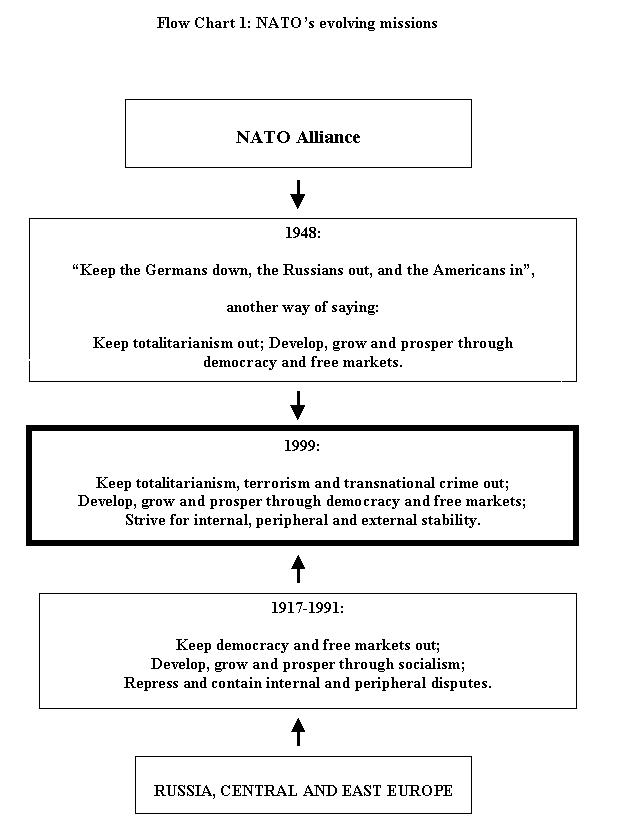

It is not difficult to see the similarities between "1949" and "1998". Just askyourself: what were and still are NATO's enemies then and now? Here is Lord Ismay’s 1948 quip that may be helpful: "… keep the Germans down, the Russians out, and the Americans in…". At that time keeping the "Germans down" meant keeping "fascism down"; "Russians out" meant "communism out"; and "Americans in" meant "freedom, democracy, prosperity, and stability in".

As the leader of the West, during this century the U.S. successfully fought wars against fascism and communism, proving that such anachronistic systems cannot sustain themselves and that they are not conducive to peace and prosperity. It was indeed a defining and fruitful victory, a victory that has been welcomed by Germans, Japanese, Central Europeans, Asians and many more. For more than fifty years now, ex-Axis countries have been demonstrating that they understand the values of peace, democracy, stability, and prosperity. Similarly, since 1991, "majority" Russia appears determined to try the best approach, the approach based on the rules of democracy and free markets.

But there is also "minority" Russia which asks: "Why NATO? Why NATO enlargement? What for?" Unfortunately, some Russians claim that the West has difficulty learning from recent history, and as a result history will repeat itself. NATO's existence and, even more gravely, NATO's enlargement, they say, is evidence that the West is preparing another invasion against mother Russia, exactly as the West did in recent past under German or French alliances. Needless to say, those few Russians ought not be afraid. They, like the rest of the world today, should see instability, extreme nationalism, and the potential resurgence of anachronistic systems as the enemy common to all, and, given recent history, especially to Europeans and Russians. An evolving NATO should not be feared by Russia or any other country. It and they face the same threats.

Flow Chart 1 (above) points out that the evolution paths of NATO, Russia, Central, and East Europe meet today in the area of a common mission. Undoubtedly, as NATO has been demonstrating for fifty years, its intention is to serve as a preventive medicine against potential instability which is undesired, not only by member states, but also by peripheral as well as external neighbors.

NATO serves as a quasi-public good for its members and as a pure public good for its non-members. It is non-exclusive in the protection it provides regardless of how much each member contributes. Simultaneously, it enables its peripheral and external neighbors (e.g. Switzerland, Austria, Sweden and even France) to free ride under its protective umbrella. With such protection, extremists or anachronists in either member or non-member nations have less potential support for a rise to power. The obvious example is the non-member nations of Bosnia and its immediate land neighbors in conjunction with recent/current events there: NATO's successful intervention not only restored order in the area, but it also prevented the outbreak of potential instability to its members, Russia's "near abroad," and possibly the entire world. The evidence clearly demonstrates that the evolving NATO should not be feared by Russia or any other nation. Instead, it should be embraced, welcomed and, if possible, assisted in the pursuit of its mission.

Naturally, one may ask: why should NATO be maintained and assisted as it pursues its new mission? The answer is easy: because it serves as a creator and protector of prosperity. It has done so during its first fifty years -- just compare West Europe’s prosperity and security levels from 1945 to 1998 to those previously achieved -- and it will be necessary in order to continue doing so in the future.

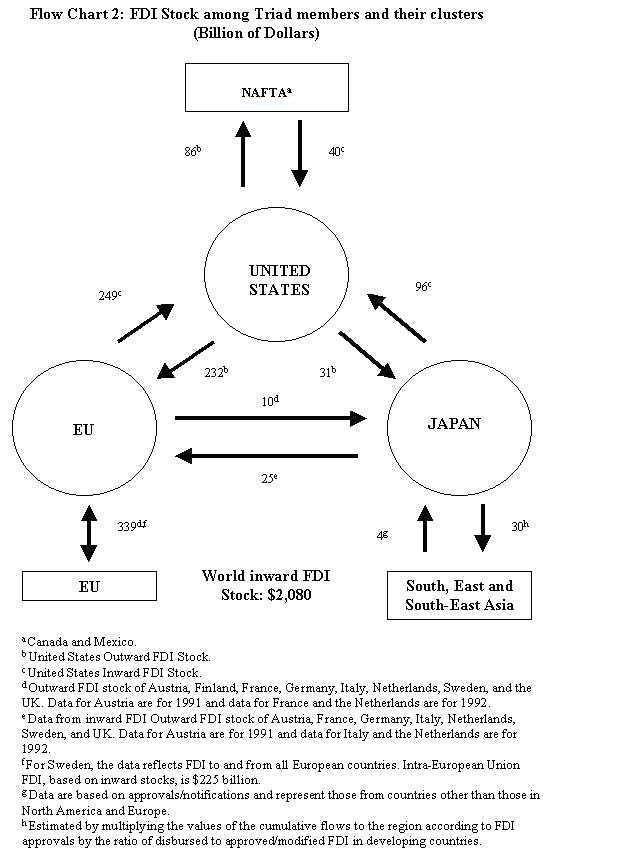

The necessity of the continuation of its new mission depends on two factors: (1) high economic interdependence between Europe (European Union – EU) and North America (North America Free Trade Agreement – NAFTA), and (2) globalization of economic activity. EU and NAFTA get richer not only from their economic interaction, but also from their interaction with the rest of the world. Thus, both factors contribute to EU’s and NAFTA’s increasing wealth levels and ever rising share of the global economic pie. Undeniably, it is not only a prosperity path that Europe and North America desire to continue following, but a path that they would like to share, under win/win conditions, with the rest of the world, especially Russia.

According to a UN report [2], out of the top 100 transnational corporations ranked by foreign assets in 1995, 78 originated from the EU/NAFTA regions, with the U.S. leading the per-country tally (30) followed by the U.K. (11), France (11) and Germany (9).

With the help of Flow Chart 2 [3], one can easily compare the degrees of interdependence between the depicted regions. The measure used is Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), and it shows that, with respect to origin and destination, investment stocks and flows are concentrated primarily in the developed world of Europe and US/NAFTA. The distribution of inward FDI stock reflects the superior market sizes of EU and US/NAFTA. The outward distribution of the same measure reflects the superior competitiveness of US/NAFTA, EU and Japan, based on their ownership specific competitive advantages.

As EU and NAFTA become increasingly more economically interdependent, borders become less meaningful, national militaries lose their state support, and the need for collective defense and security becomes vitally important and simultaneously more difficult to satisfy. Undeniably, the NAFTA and EU economies are what NATO tries to protect from the multidimensional enemies of instability, poverty, neo-totalitarianism, terrorism, and transnational crime, an enemy common to all those countries that have decided to take the "prosperity" path, the path to free markets and democracy.

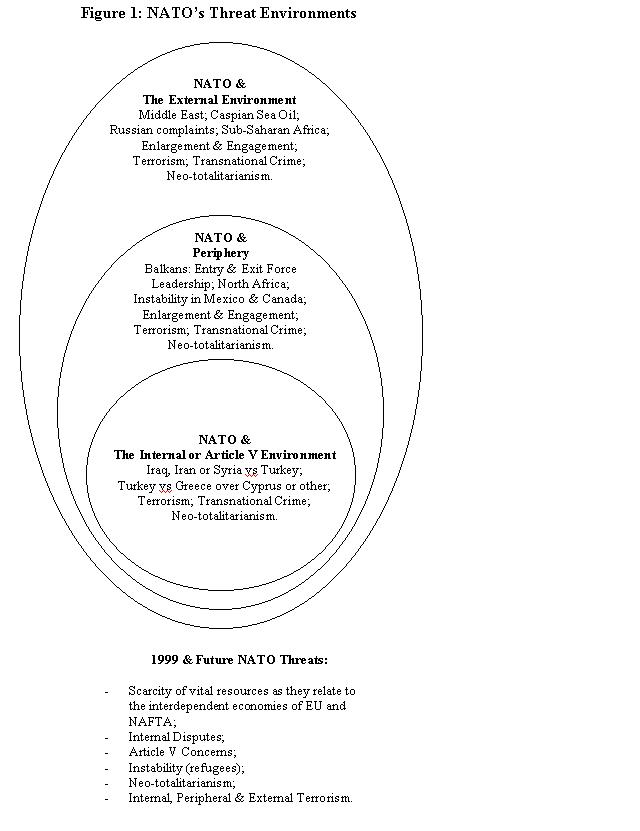

III. NATO’s ThreatsUp until the fall of communism, NATO was able to focus on the one and only significant enemy and, thus, clearly saw the line that separated the good from the bad. Today, it is not as easy to focus on today's multidimensional "enemy". There is no separating line: the enemy exists not only in NATO’s external environment and periphery, but also inside its home territory; it is a less lethal enemy, but it is one that is more pervasive and difficult to deter. Threats are both, Article V [4] (internal) and non-Article V (peripheral and external) related.

NATO’s members can be attacked at any time by external forces. This gives justification to Article V concerns and operations. Some old problems remain, and many new ones have emerged. Article V concerns exist today in NATO’s Southeast region due to possible conflicts between Iraq and Turkey, Turkey and Greece over Cyprus, or Turkey and Greece over other issues. Additionally, the Alliance is concerned about "internal" terrorism, the rising fear of transnational crime, and the spread of weapons of mass destruction.

Moreover, NATO is probably more concerned with many non-Article V potential threats and operations, ranging from the Alliance’s periphery to its external areas. In its periphery (i.e. neighboring areas), the Alliance worries about North Africa (especially Algeria), and it is involved in peace keeping in Bosnia, and it is fighting to return Kosovars to Kosovo, a province of Servia. There are concerns, too, about nearby countries and whatever comes with the expansion of NATO. NATO’s partnership building with non-member countries through various institutions, e.g. Partnership for Peace (PfP), improves the organization’s strategic reach but, at the same time, it imports their substantial problems.

In its external area (i.e. non-neighboring areas), the Alliance is concerned with Russia’s struggle for development, the possible induction of new members, and its relations with emerging and evolving institutions. Moreover, the Caspian Sea area with its significant oil reserves and its proximity to Turkey, undoubtedly vital for Europe’s future, concern NATO more than ever. Another area of concern is the vast Sub-Saharan region which, due to competing interests, may cause friction between Europeans and Americans, with damaging effects for the Alliance. Similarly, NATO may be divided over Middle East issues since, as the EU acquires more power, European and American interests in the region may diverge even more.

Figure 1 (above) summarizes the internal, peripheral and external environments. Common to all environments are terrorism, transnational crime and neo-totalitarianism.

IV. NATO’s Effectiveness

Two realities speak in favor of NATO’s effectiveness: its history in preventing the unthinkable and its current successful operations in Bosnia. In both of these realities the U.S. played and continues to play the most significant role. Naturally, one may wonder whether, as the U.S. and the other allies pursue different strategies, will the Alliance continue being effective in the future? Moreover, as the Alliance has become a desirable "club" to join, should it continue accepting new members? Are there limits as to how far it is reasonable for NATO to expand? Could continuing enlargement of NATO negatively affect the quality of the security that the Alliance provides?

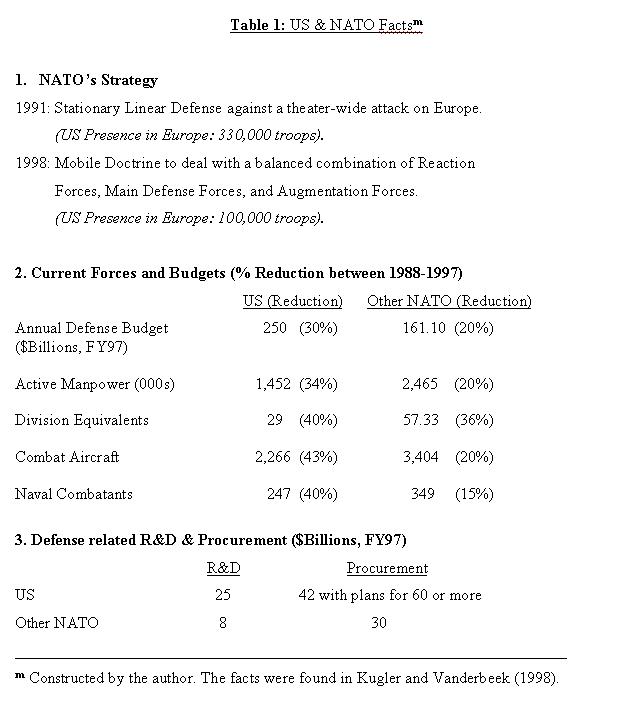

After 1991, the U.S. and NATO have been pursuing different strategies. Although both entities reduced their military budgets, the U.S. has been focusing less on Europe and more on the Middle East (primarily the Persian Gulf) and Asia (primarily Korea). Consider Table 1. Items 1 and 2 show, respectively, that NATO’s current strategy is supported by less U.S. presence in Europe, and that "other NATO" has downsized less than the U.S. Item 2 shows clearly that there are still significant defense assets on both sides of the Atlantic.

The assets of "other NATO" exceed, in quantity, those of the U.S. but, as a whole, "other NATO’ spends less than the U.S. For example, they spend annually $161.10 billion to support 2.465 million troops whereas the U.S. spends $250 billion to support 1.452 million troops. In other words, the U.S. per troop spending is more than twice as much as that of the "other NATO" per troop spending. Moreover, as item 3 of Table 1 reveals, "other NATO" spends less on both R&D and procurement relative to U.S.

The above comparisons indicate that, militarily, "other NATO" states are qualitatively inferior to U.S. These are shortcomings that have the potential to weaken the effectiveness of the Alliance in pursuit of the mission outlined above. The fact that the Alliance does its job today in Bosnia is primarily due to the input and leadership provided by the U.S. Apparently "other NATO" should make a move towards more quality. The move does not imply that "other NATO" should copy the U.S. military capabilities. It may be wiser to deploy complementary assets instead. These assets may be acquired or, if they already exist, they have to become more focused or to specialize on their competitive and comparative advantages. "Other NATO" should try to catch up with the U.S. and prepare for a challenging future. Kugler et. al. (1997) identify six areas that "other NATO" could focus on: revolution in military affairs, peace support missions, NATO enlargement, weapons of mass destruction defense, power projection outside Europe, and fair burden-sharing. Undoubtedly, those states that combine to make up the "other NATO" must become more pro-defense and more forward-looking.

Finally, the NATO partners ought to continuously try to satisfy certain alliance principles or effectiveness factors. Such an effort will enable the Alliance to remain focused, vibrant and as close to the optimum as possible. It is likely that NATO effectiveness will vary with the number of members (Optimum Alliance Size), the criteria for member selection (Minimization of Adverse Selection), the establishment of disincentives for members’ risky behavior (Minimization of Moral Hazard), and the equitable distribution of burdens (Minimization of Free Riding).

OPTIMUM ALLIANCE SIZE To what extent can NATO preserve sustainable cooperation among its members? Can such cooperation be jeopardized with the addition of new members? Is there an optimum Alliance size? Since its inception NATO’s expansion path has been controversial. But most would agree about its overall success and that even more security gains are likely possible. Success, of course, has not always been achieved in an environment of total cooperation. For example, France withdrew from NATO’s military structure in 1966; Greece withdrew from the same structure in 1974, but rejoined in 1981; Enlargement is desired more by some members (e.g. Germany) and less by others (e.g. U.K.). Realistically, cooperation cannot be taken as a given and, as history testifies, it occurs only sporadically. Thus, one can infer that reaching sustainable cooperation, is indeed a difficult objective.

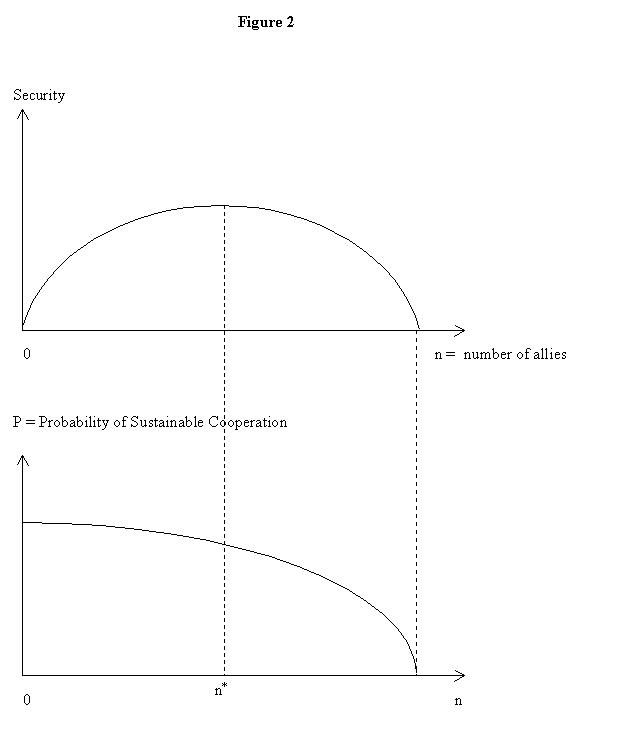

Would sustainable cooperation be affected by the induction of new members? Napoleon Bonaparte once said to the representative of an enemy, "The more (allies) you have, the better it is for me," implying that the more members in an alliance, the worse off that alliance would be. Was Napoleon right? Logically, if "n" is the number of allies and "P" the probability of sustainable cooperation, the relationship between "n" and "P" should be negative. Assuming that we have well defined security and probability functions like those in Figure 2, theoretically, an optimum number of allies (n*) corresponds to the point of maximum security from sustainable cooperation. Thus, when n is less than n* the probability of sustainable cooperation is higher but security is not at optimum. Similarly, when n is greater than n* the probability of sustainable cooperation is lower but security is not at optimum. This simple model demonstrates that, given certain functions, the optimum number of allies, n*, that maximizes security can be easily determined. But, as Kant said: "theory without data is empty." Therefore, the challenge is to empirically determine the forms of the above functions, a difficult task, or rely on alternative methodologies [5] to determine n*.

ADVERSE SELECTION Since many non-members have applied or plan to apply for membership, NATO has to be careful with its selection process. Like an insurance company, the Alliance has to minimize adverse selection, and if possible, avoid accepting lemons or bad risks. Adverse selection arises because of the Alliance’s inability to accurately distinguish between high- and low- risk new members. This inability may be due to such things as lack of intelligence information or the misinterpretation and misunderstanding of intentions. For example, the Alliance may set entry conditions in such a way so that high risk countries find it advantageous to enter and low risk countries disadvantageous to do so. Thus, if due to disadvantageous entry conditions, low risk countries do not enter, the Alliance may end up with the lemons. Arguably, Italy was a lemon for the Axis Alliance in the IIWW and the Austro-Hungarian Empire for the Triple Alliance in the IWW.

Currently, the organization attempts to minimize adverse selection by dividing prospective members into two groups: (1) those who satisfy a certain number of entry criteria and, (2) those who do not yet satisfy all such criteria. Prospective members of the first group, are encouraged to apply for full membership. Those of the second group, are encouraged to participate in the Alliance as associate members through institutions such as PfP [6]. Associate Membership institutions are primarily preparatory entities that allow qualifying countries to prepare at their own pace for full membership.

MORAL HAZARD The problem of Moral Hazard occurs when allies undertake risky action after they become full members. For instance, because a member country is under NATO’s protection umbrella, it may act in a more provocative or aggressive manner than if it were on its own. Russians are concerned about this Moral Hazard problem despite the guarantees offered by the West. They insist that the new NATO members of Central Europe, and prospective members of other ex-Warsaw Pact countries, would have more of an incentive to commit aggression against their peripheral and external neighbors’ interests under NATO than under an independent defense policy. Undoubtedly, this is a concern that we in the West ought to take seriously into consideration, especially as these ex-Warsaw pact countries develop more vital economic links with the current NATO members than with Russia.

At this time, NATO’s effort to minimize provocative behavior by its newer members, especially in its enlarged area, amounts to a non-signed promise that in the newly inducted countries NATO headquarters would not be established, strategic weapons would not be located, and stationing of forces other than the country’s own would not take place. Logically, the establishment of more disincentives for members’ risky behavior would serve as a credible guarantee to Russia and others, against the potential costs of Moral Hazard.

FREE RIDING Additionally, NATO's effectiveness depends on whether or not burdens are distributed equitably. As the concerns of the Alliance extend from its internal to its peripheral and external environments, all members are expected to add value to Article V-type defense capacity. Additionally, they will have to think more as security providers rather than security consumers.

NATO membership has the potential to be a free ride if it relies on the well known Article V "one for all, and all for one" mentality which resembles Marx's "from each according to his ability to each according to his need." Free riding is what killed communism but it won't kill NATO as long as each member considers the utility it derives greater than the cost it pays.

The Alliance brings security to old and new members but it requires equitable and credible commitments from all. From each country according to its transparent vital interests and competitive or comparative advantage to each according to its transparent needs would be more appropriate for the maximization of collective security/defense and the minimization of free riding.

A review of Flow Chart 2 reminds us that the vital, vast, and interdependent economic interest between EU and NAFTA is the real reason why Europe, Canada and the U.S. support NATO. Undeniably, the more a state's interests need protection, the more motivated the state is to contribute to an alliance of collective security or defense.

Moreover, an alliance that consists of members that are complementary to each other can more easily achieve sustainable cooperation. Complementarity will enable the allies to establish incentives for the avoidance or elimination of free riding. The formation of a vertical alliance has the potential to do so because it would distribute defense or security tasks to each country according to the country's comparative and/or competitive advantage. For example, if NATO turns into a vertical alliance, the U.S. may provide information systems, precision capabilities, space assets, and prepare the allies to make the best use of the weapons it alone can offer them. "Other-NATO" may provide firepower and infrastructure or other assets.

V. CONCLUSIONAs it was postulated above, NATO's mission is to keep totalitarianism, terrorism, and transnational crime out; and to develop, grow and prosper through democracy and free markets, as well as to strive for internal, peripheral, and external stability. NATO's attempt to reach its objectives would be hampered by internal, peripheral and external threats. Undoubtedly, the Alliance's ultimate objective is to protect the interdependent economies of NAFTA and West/Central Europe.

NATO should not be feared by Russia or any other state. Instead, the Alliance should be embraced, welcomed and, if possible, assisted in the pursuit of its mission, a mission that is shared by all, including Russia and Centeral and Eastern Europe.

NATO's mission can be carried out only if the allies remain focused, vibrant, and as close to the optimum as possible. This may be realized only if certain alliance principles, or effectiveness factors, are satisfied such as: the number of members (optimum alliance size), the criteria for member selection (minimization of adverse selection), the establishment of disincentives for members' risky behavior (minimization of moral hazard), and the equitable distribution of burdens (minimization of free riding).

Although it is not easy to empirically determine optimum size, for a start, there are numerous methodologies available that researchers could rely upon. With respect to Adverse Selection, the Alliance has established entry criteria and institutions for "Associate Membership". To deal with problems associated with Moral Hazard, NATO has announced that in the newly inducted members "headquarters", "strategic weapons," and "stationing of forces other than the country's own" is not warranted. To minimize Free Riding, allies may rely on complementarity and vertical alliance structures according to their comparative and/or competitive advantage.

Finally, although research for this paper was completed prior to the currently unfolding Balkan War and therefore, comments made about Kosovo, Yugoslavia and NATO would be highly speculative, it may be constructive to respond to a point made by a reviewer of this journal. This reviewer correctly questions NATO’s involvement in Kosovo (non-Article V territory) without a legal mandate by the United Nations (UN). In response, let us remind ourselves the precedence that the UN established in the previous Balkan War in Bosnia: after the UN attempted to deal with the ‘ethnic-cleansing-type humanitarian problem’ by itself and failed, it legally invited NATO to intervene and help in the establishment of sustainable peace for the entire region, a region totally outside Article V territory. The result of this intervention was the Dayton Peace Treaty, signed by all involved – Slobodan Milosevic included, which gave birth to a democratically ruled Bosnia. Thus, given this precedence (that is, the UN’s proven ineffectiveness in dealing with ethnic-cleansing-type humanitarian problems, and the fact that NATO had been invited to carry operations outside its territory) one could find justification in NATO’s ‘outlaw’ behavior. It appears that NATO placed more weight in doing something ‘pragmatic’ instead of ‘politically correct’; probably because the ‘politically correct’ would have caused delays and grid-lock debates. Could NATO’s pragmatic move be considered a prudent choice? Although the answer to this question, at this time, is highly speculative, it appears that the Alliance made, at least, a justifiable choice; a choice that may prove beneficial for the highly interdependent economies of NAFTA and West/Central Europe.

Click here for a view that contrasts with the author's in regard to the intervention in Yugoslavia.

1. Institute for National Strategic Studies, Strategic Assessment (1997), p. 41.

2. United Nations, UN Conference on Trade and Development World Investment Report: Transnational Corporations, Market Structure and Competition Policy (1997).

3. The same Flow Chart appears (as Figure 1) on page 107 of "World Investment Report 1995: Transnational Corporations and Competitiveness. Overview" in Transnational Corporations, Volume 4, Number 3, December 1995, UN.

4. Article V (NATO Handbook):

The Parties agree that an armed attack against one or more of them in Europe or North America shall be considered an attack against them all and consequently they agree that, if such an armed attack occurs, each of them, in exercise of the right of individual or collective self-defence recognised by Article 51 of the Charter of the United Nations, will assist the Party or Parties so attacked by taking forthwith, individually and in concert with the other Parties, such action as it deems necessary, including the use of armed force, to restore and maintain the security of the North Atlantic area.

Any such armed attack and all measures taken as a result thereof shall immediately be reported to the Security Council. Such measures shall be terminated when the Security Council has taken the measures necessary to restore and maintain international peace and security .

5. Herbert Simon’s (1968) term satisficing is an alternative to optimization for cases where there are multiple and competitive objectives in which one gives up the idea of obtaining a "best" solution. In this approach one sets lower bounds for the various objectives that, if attained, will be "good enough" and then seeks a solution that will exceed these bounds. The satisficer's philosophy is that in real-world problems there are too many uncertainties and conflicts in values for there to be any hope of obtaining a true optimization and that it is far more sensible to set out to do "well enough" (but better than has been done previously). By evaluating all possible alternatives, the computation of an optimum strategy may not be feasible when the number of alternatives is very large; e.g., in chess, the number of available plays exceeds computational limits not just for humans but also for computers. A decision maker who settles for a less ambitious result and obtains the optimum he can compute under given time or resource constraints is said to satisfice.

6. NATO introduced the Partnership for Peace (PfP) initiative at the January 1994 Brussels Summit. The initiative's intent is to increase and intensify political and military cooperation throughout non-NATO European and neighboring countries. There are 26 members (European and mostly ex-Soviet countries) and their objective is to gradually join NATO. The Alliance views PfP as an evolutionary process that helps participating countries develop the political and security requirements necessary for all of Europe. Article 10 of the Washington Treaty provides for the inclusion in NATO of other European states in a position to further the principles of the Treaty to contribute to the security of the North Atlantic area. (For more information, the interested reader may browse: http://www.calguard.ca.gov/40div/pfp.htm)

References

Primary:

Kugler, R. And Vanderbeek, T., "Where is NATO's Defense Posture Headed?", Strategic Forum, National Defense University, Institute for National Strategic Studies, #133 (February 1998).

March, J.G. and Simon, H., Organizations, Cambridge Press, 1968.

National Defense University, Institute for National Strategic Studies, Strategic Assessment (1997).

United Nations, Transnational Corporations and Competitiveness, UNCTAD, Division on Transnational Corporations and Investment, World Investment Report (1997).

Secondary:

Cronin, Patrick R. (Ed.), 2015: Power and Progress, National Defense University, Institute for National Strategic Studies (1996).

McArdle Kelleher, C., The Future of European Security, Brookings (1995).

NATO Office of Information and Press, NATO Handbook, Brussels (October 1995).

Sperling, H., and Kirchner, A., Recasting the European Order, Mancester University Press (1996).

Spiezio, K. E. , Beyond Containment - Reconstructuring European Security, Rienner (1995).

Thanks go to:

For invaluable discussions, suggestions and comments, the author is grateful to Maj. Gen. Timothy A. Kinnan, Professor William T. Pendley, Professor Ted Hailes, Col. Frank L. Belote, Dr. Michael Hickok and especially Dr. Barry R. Schneider. Additionally, I would like to thank the anonymous reviewers of this journal; their questions and requests have added to the value of this paper. For all errors, the author remains solely responsible.

The graphic used to create the title graphic above was obtained from NATO's site on the Web.