![]()

|

PART 1: DESCRIPTION OF THE PROBLEM |

Adam J. Koch akoch@swin.edu.au is on the faculty of the School of Business, Swinburne University of Technology, Hawthorn, Victoria. Australia.

|

Summary The quality of strategic marketing decisions is to a large extent dependent on

This article looks into the issues of validity and reliability of a crucial tool of strategic analysis, SWOT. It utilizes results of authorís study conducted in the second half of the 1990s of the relevant practice as presented by his Australian postgraduate students enrolled in business management courses. The main argument of this paper is that it is certain misconceptions held about the nature of SWOT, poor quality of input and inadequate skills of those who use SWOT, rather than properties of this tool, that are to blame for most cases of its less than successful implementation. To help organizations enhance their SWOT analysis, a corresponding model of this analytical process will be introduced in the second part of this paper.Part 2, Fundamentals of Enhancement , will appear in in January 2001. |

|

INTRODUCTION |

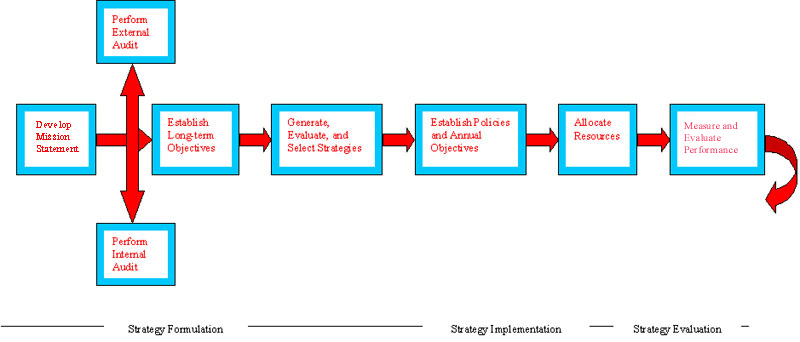

A tool of situation analysis, SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats) is used in the preliminary stage of strategic decision-making [Johnson et al 1989] where it provides the basic framework for strategic analysis. [1] SWOT generates lists, or inventories, of strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats. ( See Figure 1 below.) Organizations use these inventories to generate strategies that fit their particular anticipated situation, their capabilities and objectives (Bourgeois 1996; David 1997; Miller and Dess 1996; Pearce and Robinson 1997; Thompson and Strickland 1998).[2]

Figure 1

Basic Framework For Strategic Analysis

For all its simplicity, SWOT is often used poorly, and for purposes different from those it has been designed for. An investigation of the relevant practice by UK companies (Hill and Westbrook 1997) showed that SWOT is very often looked upon as a basic analytical structure only, or used as a way of launching a wide-ranging group discussion about a companyís strategic position. In these cases, SWOT is usually not linked, at least formally, to any subsequent strategic planning application.

Hill and Westbrook based their criticism of SWOT on cases of strategic planning malpractice. This begs the asking two fundamental questions: Is it appropriate for the judgment of the suitability of an analytical tool to be exclusively based on cases of its misapplication and poor usage? And, should any tool be blamed for the misconceptions, negligence and errors of those who use it? It appears that the answers to both of these questions should be in negative. A far more appropriate and reliable basis on which one could form such judgment and propose how SWOT ought to be used in strategic planning would have to contain cases of both exemplary, and flawed, SWOT usage.

|

TWO BASIC CRITICISMS OF SWOT |

There are two main grounds on which SWOT has so far been criticized. Firstly, much of the reported usage of SWOT (Baramuralikrishna and Dugger 1998; David 1997; Hill and Westbrook 1997; Johnson et al 1989; Thompson and Strickland 1998; Wheelan and Hunger 1998) suggests that this usage rarely amounts to much more than a poorly structured, very general, hastily conducted exercise that produces unverified, vague and inconsistent inventories of factors regarded by the proposing individuals as most important components of their organizationís strategic situation.

The way SWOT analysis is often conducted does not allow for proper communication, discussion, and verification of all external and internal factors proposed by all involved. On such occasions, SWOT results prove less reliable an input to the strategy generation process than they are capable of being. Still worse, as documented later, the results of SWOT analysis are sometimes never meant to be used as an input to the strategy generation process. If that is known, or anticipated, by those involved in SWOT analysis, the quality of their inputs will most likely suffer and be lower than otherwise possible, and desirable.

It is clear that imprecise or vague reference in such an analysis to factors external and internal to an organization will always detrimentally affect communication and verification of proposed factors and thus lead to inferior outcomes of strategic analysis. It appears that this common flaw in SWOT analysis is caused mainly by misconceived SWOT deployment, insufficient levels of skills and diligence, and strategic information gaps. [Hill and Westbrook 1997] Relevant examples of such flaws in SWOT analysis are shown later in this article. In general, malpractice of this kind may be quite detrimental to the performance and strategic position of the affected companies. Any SWOT analysis that shows such grave flaws should be considered inadequate.

Other criticism (Mintzberg 1994) suggests that SWOT is the main cause of what is considered there an excessive formalization of the strategy making process. While it is true that many organizations develop excessively formalized approach to strategic management, regarding SWOT as the cause of this over-formalization, or even its symptom, would clearly be a mistake. The blame for an excessive formalization of the strategy making process by some organizations should be laid instead at the door of those who misconceive the role of this tool, misapply it, or substantially misinterpret SWOT results.

|

METHOD |

This paper proposes a clarification of the SWOT concept and looks into cases of its misuse. It points out the misconceptions about this tool and then suggests how to eliminate its established application weaknesses. This lays the groundwork for the presentation in the second part of this paper of how SWOT ought to be used to produce reliable inputs into strategy generation. [3] In acknowledging its general usefulness, its comprehensive character and its pivotal role in the strategic planning process, it is argued here that SWOT could live up to its potential and influence positively the quality of generated and selected strategies. [4] Further enhancement of the practice of strategic analysis and planning depends, among other things, on an improved understanding of SWOTís capacity and limitations. A brief study of the various critical evaluations of SWOT (David 1997; Dealtry 1992; Hill and Westbrook 1997; Johnson et al 1989; Wheelen and Hunger 1995; Weihrich 1982) affords the much-needed platform to propose the way to enhance SWOT analysis.

To add to, and further diversify, the factual basis on which to base recommendations, the author has also drawn on some of his postgraduate teaching experience. Most of this experience comes from the postgraduate subject Marketing Management 2 taught at the authorís university. Students in this subject represented various, mostly tertiary, Australian industries. On average they had some twelve years of business experience. Most of them represented middle level of management. Students enrolled in this course in 1997 and 1998 submitted their written SWOT analysis of their organizations. [5] Subsequently, students were encouraged to use their teacher's feedback (See Appendix A.) to then reflect on the flaws, if any, of their SWOT analysis. This teaching experience has produced a major part of the SWOT usage evidence utilized in this paper. [6]

|

MISCONCEPTIONS OF SWOT'S ROLE |

Many complaints about SWOT 's performance seem to be based on misconceptions about its role. Some of these suggest poor analytical skills of some of those involved in strategic planning process, or their poor judgment. Other examples show inadequate amount of information about the company and its external environment. Still other examples document poor quality of information relied upon in some SWOT analyses. It follows then that it is rather the managers' misconceptions, misapplication of SWOT and less than diligent execution of strategic analysis than the inherent characteristics of the tool, that ought to be blamed for the prevalent industry perception that SWOT generated inputs are rarely sufficiently valid and reliable. We first discuss the misconceptions.

SWOT commences from drawing up a list of current company strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats. What often gets forgotten, though, is that in order to help generate suitable strategies for a certain period, SWOT needs to revise this original inventory to arrive at one that would reflect accurately enough the anticipated company strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats for that period (Dealtry 1992). Neglecting this leads to generating strategies based on the current (or even past), and not the future, as appropriate, situation. If a considerable change in the organization's environment is imminent, strategy selected on the basis of the immediate past situation is very likely to be ill suited to the changed state of environment.

Second, simple frameworks as SWOT cannot, of themselves, ensure the necessary rigour of strategic analysis. To expect otherwise is fallacious. SWOT helps to spell which strengths the organisation should be building its future on, impact of which weaknesses needs to be minimized, what opportunities ought to be seized, and what threats need to counteracted (Baramuralikrishna and Duggar 1998). The available evidence (Hill and Westbrook 1997) suggests that, unless SWOT is used properly, it is likely to produce unreliable inputs into strategy generation. This would explain the claim from some academics (e.g. Hill and Westbrook 1997; Mintzberg 1994) and business people as well that as a tool of strategic analysis SWOT has got serious flaws.

Third, SWOT is in practice rarely deployed at lower than the corporate level. A typical situation is for SWOT to be done for the corporate level only. This often produces a risk-laden fallacy that each strength and weakness, regardless of scenario, is relevant to and equally significant for all Strategic Business Units (SBUs) and products the company makes or sells. Such fallacy obfuscates differences between situations of various products/services and can often lead to wrong strategies being selected for individual SBUs, product lines, or indeed the entire company. By producing a single SWOT for one organization level only, companies will deny themselves opportunity to fine tune strategies to the particular requirements of SBUs, product lines, and geographic markets. Recognition of the importance of conducting SWOT analysis at various levels of an organisation is reflected in one of the rules of the proposed SECURE model presented in the second part of this article.

Fourth, to evaluate the size of its competitive gaps and leads, the company needs to know the relevant performance levels of all its close competitors. Yet, the relevant business practice is often different. Many companies find it too difficult to collect comprehensive, unbiased and up-to-date information on all relevant facets of competitor performance. Sometimes, the difficulties begin at the level of defining who all their close competitors are. Volatility of the competitive environment and differing judgments on factors by various individuals involved in SWOT analysis often aggravate this problem.

Fifth, SWOT inventories are rarely modified for alternative strategy options. All such oversights are quite remarkable in that few would disagree that the meaning and significance of any weakness or strength is strategy-specific. Let us imagine, for instance, a company that has sold organically grown vegetables and fruit of superior appearance and freshness at premium prices accepted by some market niches. If such a company all of a sudden switches to a mass, rather than niche, marketing strategy, its assumed technological strengths are likely to carry, at least for some time, significantly less weight with those of their potential, or actual, consumers who buy largely on price and accept average appearance and freshness.

Sixth, the reference to the current, rather than to the anticipated future, competitors' performance levels is another popular misconception. Some companies are slow to adapt benchtrending, rather than benchmarking, as the more accurate, and more appropriate, strategic planning tool. They develop their strategies on the implicit, or arbitrary, assumption that their current strengths and weaknesses will retain their validity and currency throughout the entire period during which new strategies are to be pursued. Such a practice contradicts the very logic that underlies an effective strategy generation: the choice of strategy needs to be based on the anticipated future situation, not on an analysis of the current one. The (perceived) level of difficulty in obtaining a complete, unbiased and up-to-date prediction of all relevant facets of competitive performance could be, on the strength of authorís experience the main cause of such a neglect.

Further, local benchmarking/benchtrending is only justified where the local character of competitive comparisons matches both the current and the anticipated geographic scope of competition. Yet, contrary to this rule, local rather than global benchmarking/benchtrending is still the preferred way of arriving at the company relative performance rankings. However, as more and more industries in an increasing number of countries realize they face global, rather than local, competition, this inadequacy is likely to become increasingly rare.

Cases of blinkered and short-sighted competitive analysis can often be explained by

The list of common SWOT related misconceptions is presented below in Table 1.

Table 1

Common Misconceptions about SWOT

|

Misconception |

What's wrong about it |

Consequences of this misconception |

|

SWOT has got an analytical capacity of its own |

SWOT is essentially only an analytical framework of the internal and external audit. |

Any SWOT generated inputs may be wrongly considered a reliable basis on which to found strategy making. |

|

SWOT should only be done at, and for, the corporate level |

Most organisations follow, at any point in time, a number of strategies, some of which may relate to sub-corporate levels of activity (SBU, product line etc.). |

If the deployment of SWOT is restricted to the corporate level of strategic analysis, SWOT outputs will often be misleading in that they will suggest that eg. all strengths and weaknesses are equally relevant to all SBUs and products; another consequence is that the opportunity learn from conducting a series of SWOT based analyses at various corporate levels and in various divisions may be foregone. |

|

SWOT is based on the current competitive situation |

If SWOT is done to prepare vital inputs to assist in strategy generation, then the only truly relevant reference is the future competitive situation anticipated in the period the strategy is formulated for. |

The strategies selected will be wrongly based on the current, rather than on the anticipated future, competitive situation; should any significant changes occur to the list, and the significance, of current strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats, the strategy may turn out to be a poor fit, and a failure. |

|

The content of SWOT generated lists does not depend on the strategy the organisation would implement |

Different strategies may depend for their success on different strengths and address different opportunities; the degree of this dissimilarity will depend on the underlying key success factors for these alternative strategies. |

The relevant inventories proposed at the outset of the strategy making process are very rarely strategy-specific; they also would normally not be revised after future scenarios have been produced and the anticipated strategy performance under individual scenarios examined. |

|

The benchmarking/ benchtrending can be based on the current list of close competitors |

The strategic analysis should foresee the new competitive threats and new entrants into the company's markets; the picture of competition must be brought up-to-date and include instances of hypercompetition. |

Companies guilty of such an oversight will be unable to counteract new entries and may find themselves ill-prepared to find an effective long-term strategic response to the new competitive structure and patterns, as well as to the competitive strengths of new entrants. |

|

The benchmarking/ benchtrending can be based on the local market |

The increasing globalisation of competition makes it an imperative for many companies to global benchmark/trend. |

Companies that rely on local benchmarking/trending will not develop objectives and strategies aimed at achieving/sustaining international competitivenes. |

Thorough and discerning examinations of the relevant malpractice (See eg. Hill and Westbrook 1997; Johnson et al 1989, Weihrich 1982.) have shown that the task of defining company strengths, weaknesses and then relevant opportunities and threats is more difficult than most would assume. Enhancement of the relevant practice depends largely on:

An adequate verification of all proposed SWOT items will also require shared reflection of several process participants and stakeholders (Dealtry 1992). The requirements for shared reflection are manifold. For instance, Baramularikrishna and Dugger (1998) mention that many proposed SWOT items strongly reflect a person's existing position and viewpoint that, as they suggest, could be misused to justify a previously decided course of action. They also remind that the same events can be seen as opportunities by some, and threats by other, and that some SWOT contributors will have the tendency to follow the 'fit' rather than the 'stretch' format in their strategic thinking. The latter phenomenon is likely to lead to oversight of new opportunities for the company.

Johnson et al (1989) develop further the original Weihrich's concept and provide users of SWOT with some practical guidelines. They warn that opportunities and threats should not be taken as absolute. For instance, after one has considered the resources of the organization, its culture, expectations of its stakeholders, the strategies available and their feasibility, one may often realize that what at first appeared to be an opportunity is indeed a threat to this organization. Further, they suggest that SWOT be done in a sequence of steps:

Of particular value is the emphasis Johnson et al put on the importance of context for the evaluation of relevance and significance of strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats in developing new strategies.

|

DEFINING FACTORS IN SWOT ANALYSIS |

The task of defining situational factors is a great deal more difficult than most would assume. The common flaws in this area include:

The causes of these flaws are manifold. Wrong classification of factors may come about due to inadequate discernment of analysts or their neglect of the task. Too broad description of factors may be the result of emulating similarly broadly formulated quasi-inventories found in some textbooks (10) or inadequate commitment of the part of strategic analysts. A vague description of factors may come about due to the absence of critical review of all proposed items. Finally, the failure to clearly define the relevant strategic planning horizon may be often caused by poorly developed strategic frameworks, information gaps and deficient strategic analysis commitment.

|

DEVELOPING A SWOT INVENTORY |

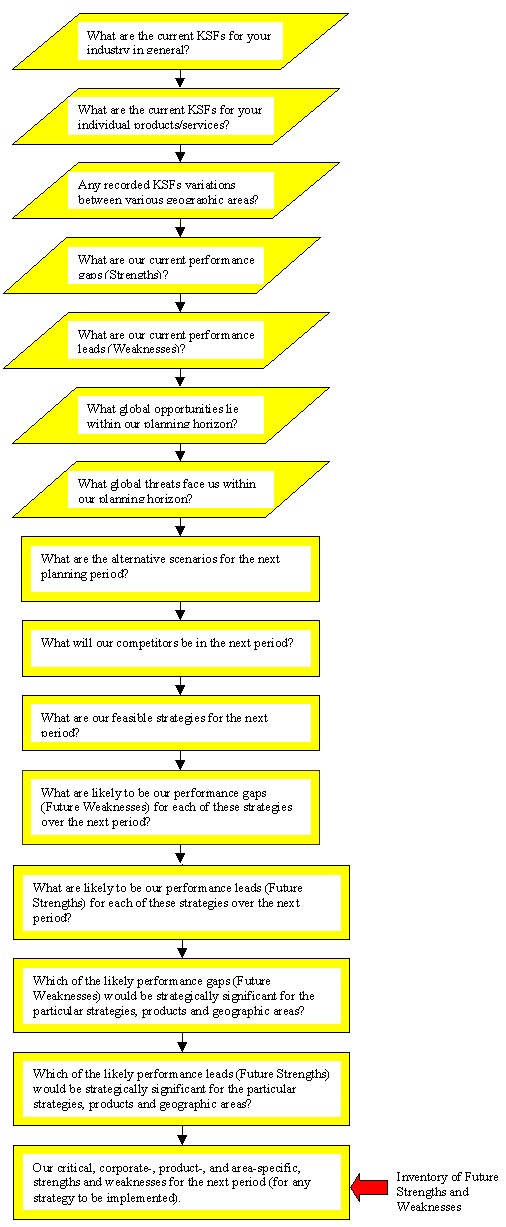

A comprehensive, well defined, properly verified and thus reliable SWOT inventory is a major determinant of the outcome of strategy generation, strategy selection and implementation. How could one ensure that SWOT inventories are brought up to date and remain strategically relevant? Figure 2 below suggests certain logic, or sequence of steps, to be followed to accomplish this task:

Figure 2

Steps To Be Followed

Various aspects of company performance may have competitive significance. Examples of these are: market responsiveness, rate of innovation, reliability of products, cost reduction, corporate - and product - image management, efficiency of logistics, customer retention and corporate learning. It is obvious that company performance in those areas, as represented by selected parameters, can change in time. The same applies to the performance of company competitors. If this is so, the relative levels of performance will also vary between periods.

Company A has a considerable advantage over company B in lower production costs, but company B is about to commission its new plant based on the newest, most efficient technology. If this is so, company B may not only be able to eliminate its own respective weakness, but may indeed enter the new period with a brand new strength in cost advantage over Company A. Take a case of a single paper mill company that has just supplanted its antiquated machine with a new one that is much wider, faster, has vastly superior production capacity, reduces the down-time by a considerable margin, and produces superior quality of newspaper grade of paper. The resulting impact on the competitiveness of such a company could be quite dramatic.

Not less importantly, new competitors entering the industry and the associated changes in the competitive patterns in the industry may result in some critical strengths of company A losing their former strategic significance. For instance, companies may retain their original technological superiority over most or all of their competitors, but this superiority may in time diminish, or lose altogether, its significance. Introduction of industrial robots to the car-making industry has had a considerable effect on the relative quality of car finish. Leading the world in deployment of robots in coating, painting and assembly of cars, Japanese carmakers were able to more quickly catch up with and even better the standard of car finish of a vast majority of European and American companies. And yet thirty years ago the latter had a vast experience advantage over their Japanese counterparts in the traditional car finishing and assembly technologies.

The likelihood of a strategist overlooking the impact of these competitive changes on the importance of individual strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats for the company is considerable whenever the quality of strategic analysis is wanting. Some new opportunities and threats may put premium on certain skills that were considered of lesser importance, or even ignored, just a few months ago. Take, for instance, the vastly increased importance of WWW site editing capacities in a successful marketing of higher education. Shifts in the importance of opportunities and threats will often produce shifts in the ranking of strengths and weaknesses, compared with the initial situation. These may lead to some strengths and opportunities being dropped by an organization from that inventory, following their loss of significance for strategy generation purposes.

Similarly, the composition of inventory may change following inclusion of new opportunities and dropping of some old ones. Also, ranking of inventory items will often change.

Some other criticisms of SWOT take their roots from fundamental misconceptions about its role in the strategic management process. As mentioned earlier, SWOT is a framework within which companies gather information about their external and internal environments. For this information to be reliable in strategy generation and selection, it needs to conform to certain rules, which are inferred from a proper reflection on its role. Yet, whenever the quality of SWOT analysis is clearly inadequate, relying on its outcomes may bring company more harm than benefit, in terms of generation and selection of strategies.

To Be Continued.......

In Part 2 of this paper, which will appear in January 2001, a SWOT enhancement framework based on the analysis presented in this first part of the article will be provided.

APPENDIX A

MARKETING MANAGEMENT 2

ASSIGNMENT 1: SWOT analysis revisited (individual)

Students will have acquainted themselves with SWOT as a basic tool of strategic analysis during their Marketing Management 1 classes. SWOT provides essential inputs into the strategic analysis and strategy selection processes, some of which will be studied later in BM603 Business Policy. For SWOT to fulfil its role much information must be gathered from external and internal environments of the company. This information must be checked, among others, for its sufficiency, recency and objectivity.

In this assignment each student selects a company (their current employer or any other company they know well enough) and then conducts SWOT analysis based on the instruction obtained during Week 2. This instruction will show you all major pitfalls in SWOT analysis. They need to avoid these in their assignment since each of these may cost them valuable points. Preferably, the selected company should already be, or likely to become, involved in international marketing within the next three years.

The purpose of this assignment is for the student to demonstrate their mastery of that particular analytical tool which includes capacity to avoid all those pitfalls of SWOT analysis which will have been discussed during the second session (see subject schedule). Students should take care to present the business environment, and in particular, its competitive component, in sufficient detail for the reader to be able to verify their SWOT propositions. For the same reason they must refer in their assignment to an explicit, or implicit, strategy pursued by their organization.

Students are neither required to develop TOWS matrix, nor need they make any recommendations with respect to the strategy. It is important, however, that whenever they ascertain significant differences between the outcomes of their SWOT analysis for the domestic environment and those referring to a global environment, they note, and explain, these.

To keep their report within the word limit, students should put all source information, and, in some cases, the table(s) containing their companies suggested strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats, into appendices. The main body of their report should contain only brief outline of the company background, its strategy and a succinct account of findings and observations they consider most important. Some of those will refer to the importance of individual (and combinations of) strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats for the strategic performance of the company.

Strategic management textbooks, such as the one by David, will help maintain the necessary methodological rigour. As this assignment provides some essential inputs into the subsequent assignments, high quality of analysis here will make the subsequent assignments in this subject so much easier to do.

Word limit: 1000 words (excluding tables and appendices with raw data).

Feedback - Assignment 1

SWOT analysis revisited

Studentís name: ..................................................................

In this assessment you may get 5 -15 points deducted for each of the below-mentioned flaws uncovered in your report, and 2-5 points added in acknowledgment of some particular strengths of your report. Values of penalties and bonuses depend on the significance of each of them for the quality of inputs derived from your situational analysis. The number of times you commit the same kind of error will influence the penalty value.

|

No |

Penalties |

Value |

Evidence |

Comments |

|

1. |

Wrong classification of factors (external/internal) |

--- |

--- |

--- |

|

2. |

Too general definition of individual factors |

--- |

--- |

--- |

|

3. |

Vague description of individual factors |

--- |

--- |

--- |

|

4. |

Ill-defined market boundaries and/or its basic structure |

--- |

--- |

--- |

|

5. |

Static or a-chronic approach to situational analysis |

--- |

--- |

--- |

|

6. |

Insufficient characterization of the competitive environment |

--- |

--- |

--- |

|

7. |

Failure to name, or insufficient reference to competitors |

--- |

--- |

--- |

|

8. |

Failure to support major strengths and weaknesses |

--- |

--- |

--- |

|

9. |

Failure to refer the analysis to an existing (explicit or implied) organizationís strategy |

--- |

--- |

--- |

|

10. |

Scope of your analysis too wide product-wise (heterogeneous frame of reference) |

--- |

--- |

--- |

|

11. |

Failure to present, or insufficient information on, the organizationís product/service profile. |

--- |

--- |

--- |

|

12. |

Providing outdated information |

--- |

--- |

--- |

|

13. |

Failure to relate to global influences on the industry and organisation |

--- |

--- |

--- |

|

A |

Penalties total: |

--- |

--- |

--- |

|

B |

Score after penalties: (100 - A)=B |

--- |

--- |

--- |

|

Bonuses (2-5%) |

Value |

Evidence |

Comments |

|

|

1. |

A modified, customized form of analysis or data presentation |

--- |

--- |

--- |

|

2. |

High quality benchmarking effort (S,W) |

--- |

--- |

--- |

|

3. |

Strong support offered in Appendices for proposed factors |

--- |

--- |

--- |

|

4. |

Comparison of the impact of individual opportunities and threats on the company and its competitors |

--- |

--- |

--- |

|

5. |

Comparison of domestic and global critical success factors |

--- |

--- |

--- |

|

6. |

Comparison of company strengths and weaknesses before and after a major change in external environment |

--- |

--- |

--- |

|

7. |

--- |

--- |

--- |

|

|

8. |

--- |

--- |

--- |

|

|

9. |

||||

|

C |

Your bonuses have total value of |

--- |

--- |

--- |

|

Your ultimate score is (B+C): |

--- |

--- |

--- |

Other comments: ...........................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

Yours standardised marks (out of 30): .....................

Instructorís signature: ..............................................

ENDNOTES

1. Throughout this paper, all references to strategic management process, or its enhancement, apply to strategic marketing as well. As all phenomena discussed and solutions proposed in this paper have strategic management ramifications, this author found it more appropriate to use the more general, rather than the narrower, reference so as to present a more holistic perspective on the problem.2. One of the cues that could support the claim that strategic planning outcomes in an organization are of high quality could be an evidence of a sustaining good fit between, on one hand, its external and internal factors and, on the other hand, strategic objectives pursued by that organization.

3. This obviously does not mean that SWOT should constitute the only input into strategy generation. Indeed, this author accepts Mintzberg's (1994) argument that an excessive reliance on SWOT in this respect is as a strategic planning malpractice. It is this author's view that that a superior quality of strategic analysis can only be achieved when a sufficient diversity of experiences, perspectives and approaches, as well a abundant internal cognition, bear on the outcomes of strategic analysis and strategy generation.

4. Students came from just over 100, mainly Melbourne-based, organizations: financial services, retail, health, hospitality, manufacturing industries and public authorities have had the largest enrolment shares in the Graduate Diploma in Business Administration course run by the university.

5. Due to the confidentiality clause and ethical considerations, no quotations that could help identify organizations or authors of SWOT usage examples provided in the assignment may have been provided in this paper.6. Hill and Westbrook (1997) point out, for instance, that the distinction between internal (strengths and weaknesses) and external factors (opportunities and threats) is not always preserved; some factors end up being classified erroneously (eg. a strength defined as an opportunity). Some authors (David 1997; Dealtry 1992) note, however, that some changes to the external environment may be perceived at the same time as threats by some people, and opportunities - by other; also, individual perceptions of factors are subject to change.

7. Hill and Westbrook 1997 give a few examples of too broad references: Ďhigh stocksí, Ďlong lead timesí and Ďnot innovative enoughí; this author has also found many such references in his postgraduate studentsí assignments, eg 'distribution' or 'promotion' used to define some of the studentís company's strengths or weaknesses); obviously, broad references make it very, or too, difficult for third persons to ascertain the exact character of the suggested weakness or strengths, and verify the soundness of the relevant claim.8. Hill and Westbrook 1997 mention in their paper commonality of failure of SWOT analysis to refer to concrete products, geographic territories or uses of products etc. This often leads to erroneous assumptions of general, rather than specific, applicability of proposed strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats. As a result these are wrongly regarded as corporate, and not SBU, or product situational characteristics.

9. Managers often fail to appreciate that most SWOT lists provided in the textbooks are hardly proper SWOT inventories, as they are not based on a complete and sufficiently deep analysis of the competitive situation of any company by people who have adequate level of the specific market knowledge.

SOURCES

Baramuralikrishna, R. and J.C.Dugger (1998). "SWOT Analysis: A Management Tool for Initiating New Programs in Vocational Schools". Scholarly Communications, University Libraries. http:// vega.lib.vt.edu/ejournals/JVTE/v12n1.

Bourgeois III, L.J. (1996). Strategic Management: From Concept to Implementation. The Dryden Press, Fort Worth

David, F. (1997). Strategic Management. 6th ed. Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River N.J.

Dealtry, T.R. (1992). Dynamic SWOT Analysis. Dynamic SWOT Associates, Birmingham, UK.

Hill, T. and R. Westbrook (1997). "SWOT Analysis: It's Time for a Product Recall", Long Range Planning, Vol.30, No.1, pp. 46-52.

Johnson, G., K. Scholes and R.W. Sexty (1989). Exploring Strategic Management. Prentice Hall, Scarborough, Ontario.

Mintzberg, H. (1994).The Rise and Fall of Strategic Planning,. Prentice Hall, Hemel Hempstead.

Pearce, II, J. A. and R. B. Robinson, Jr. (1997). Strategic Management. Formulation, Implementation, and Control. 6th ed. Irwin, Chicago.

Wheelen, T.L. and J.D.Hunger (1998). Strategic Management and Business Policy, 5th edition, Addison-Wesley, Reading, MA.

Weihrich, H. (1982). "The Tows Matrix - a Tool for Situational Analysis". Long Range Planning, April 60

The spelling of words in this article are those used in the United States. In some cases this differs from Australian practice.