The Concentric Support Model: A Model for the Planning and Evaluation of Distance Learning Programs

Elizabeth Osika, Ph.D.

Chicago State University

eosika@csu.edu

Each year, the number of institutions offering distance learning courses continues to grow significantly (Green, 2002; National Center for Educational Statistics, 2003; Wagner, 2000). Broskoske and Harvey (2000) explained that "many institutions begin a distance education initiative encouraged by the potential benefits, influenced by their competition, and prompted by fear of not being involved in distance education" (p. 37). These are just some of the reasons the percentage of higher education institutions offering distance learning programs exceeded 56% (n = 2,320) in 2000-01 (NCES, 2003). However, many programs begin without sufficient planning (Broskoske & Harvey, 2000; Katz, 2003) or are operating without the necessary support systems in place for continued success (Levy, 2003). In fact, what is necessary to support a distance learning program is a topic a few articles discuss (Benke, Brisham, Jarmon, & Paist, 2000; Phipps & Merisotis, 2000; Western Cooperative for Educational Telecommunications, 1999), but do not cover adequately, as the support of the program is not the articles' primary focus. This study addresses this void by identifying the various elements necessary to support a quality distance learning program through the introduction of the Concentric Support Model; a tool institutions can use in the planning and evaluation of their distance learning program.

The Definition of a Quality Distance Learning Program

Before a discussion can begin regarding the elements necessary to support a quality distance learning program, this concept needs to be defined. Therefore, the following definition is offered:

A quality distance learning program focuses on and supports the needs of the people it is intended to serve. Therefore, it has at its core the interaction between faculty and students, surrounded by pedagogically appropriate content presented through a stable technology platform that is supported, both technically and programmatically, to provide knowledge and/or training that is accepted and desired by the larger community (Osika & Camin, 2002).

This definition illustrates a quality distance learning program does not stop at the classroom. The classroom is where most institutions begin, and some frequently end; however, if a quality distance learning program is to be realized it must be seen as an important initiative supported and sustained by the entire institution (Levy, 2003).

Literary Foundation of the Concentric Support Model

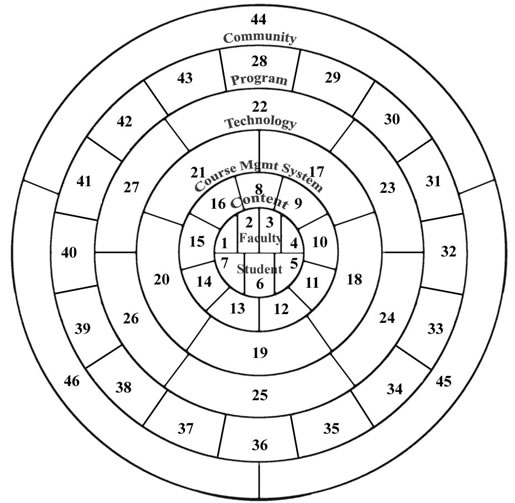

A review of the literature suggested a variety of elements necessary to support a distance learning program. Using the above definition as a guide, these elements, described in detail below, were grouped into seven broad categories which provided the base structure of the Concentric Support Model (see Figure 1):

• Faculty Support

• Student Support

• Content Support

• Course Management System Support

• Technology Support

• Program Support

• Community Support

Figure 1: Base Structure of the Concentric Support Model

Faculty Support

The core of all distance learning courses is the faculty who teach them. Therefore, it is vital faculty are successful online instructors. The literature identifies four elements that may help facilitate the success of the faculty. First, Levy (2003) identified the need of faculty to have adequate technology skills. He stated that in order to be successful teaching online, an instructor must feel comfortable manipulating files, working with email and course management tools, and troubleshooting hardware and software problems. This last aspect is especially important because faculty often become the first line of support for their students' technical difficulties (Levy, 2003).

Second, the necessary technology must be easily accessible by the faculty. It should not be a challenge for the faculty member to get access to the equipment they need to teach online (Morgan, 2000). Faculty need easy access to computers, adequate bandwidth, and a host of various peripherals and software, which may include scanners, digital cameras, color printers, and image editing software.

Third, faculty must be educated and knowledgeable about online pedagogy. "Without the provision for faculty development with distance learning, the venture will undoubtedly fail" (Morgan 2000, p 16). The teaching environment changes when moved online; however, many instructors simply "gift wrap" their courses by wrapping their traditional teaching methods with technology (Weston & Barker, 2001). Katz (2003) referred to this phenomenon as "paving the cow paths" (p. 56). He purported that, only through the development of the faculty will instruction begin to fully utilize the potential technology offers.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, faculty must be motivated to teach online. As Springer and Pevoto (2001) aptly pointed out, "[faculty] do not necessarily have to be experts in the areas of distance learning; however they must be willing to learn a new methodology, try the methodology, be willing to accept the challenges, and move on" (p. 48). The institution needs to make sure this motivation is supported with a proper reward structure or faculty will become disheartened by the amount of time and the complexity involved with teaching online (Morgan, 2000).

Student Support

Students participating in distance learning programs have requirements similar to the faculty who teach, in that they need to be technically competent, have easy access to technology, and be motivated to learn online (Carlson et al., 1998; Palloff & Pratt, 1999; Osika & Sharp, 2002). It is well documented students must have a minimum technical skill set to succeed in a distance learning classroom (Carlson et al., 1998; Palloff & Pratt 1999; Osika & Sharp, 2002). As independent learners, physically separated from their instructors, it is vital that technology does not become a barrier. Students must be comfortable and capable of performing common tasks, such as sending and receiving emails and attachments, using a word processor, and locating information online (Osika & Sharp, 2002).

Students also need easy access to technology (Spitzer, 2000; Palloff & Pratt, 1999) and the motivation to learn online (Palloff & Pratt, 1999; Roblyer & Ekhaml, 2003). Unlike a traditional classroom, students have to assume a higher level of responsibility for their learning. They need to be responsible for actively engaging with the technology, content, instructors, and other students. They also must seek out clarification and feedback on their own, as there is not a predefined time where answers are immediately available, as in a traditional face-to-face classroom (Roblyer & Ekhaml, 2003). Without the motivation to engage in these activities, student success is unlikely.

Content

When moving beyond individual characteristics to the content of the actual courses, the primary concern is that the content allows for and promotes interactivity. This interactivity needs to occur between students, between faculty and students, and between the students and the content (Carnevale & Olsen, 2003; Distance Education Report, 2000; Palloff & Pratt, 1999; WCET, 1999).

In terms of interaction between students, Belanger and Jordan (2000) reported on a study which determined the lack of student to student interaction can be a major problem, as this is an essential element in the learning process according to various educational theories. They also found interaction between faculty and students was essential for feedback. "Instructors need feedback from learners to ensure comprehension of material and to obtain information on their own performance in delivering the material. Learners, on the other hand, need feedback from the instructor on their achievement in the classes they take" (Belanger and Jordan, 2000, p 22). Spitzer (2000) provided confirming evidence in a review of his own experience, where the factor that made the most difference in terms of student success, as measured through dropout rates, was the amount of online interaction between him and the student. Finally, the content must engage the student in interactive activities. Carlson et al. (1998) pointed out that for success, "rather than designing instruction that is intended to deliver information to the learner, it is necessary to design instruction which engages the learner in interactive activities" (p. 142).

Aside from the interactive nature of the course there are some basic instructional guidelines that the content should follow (Dick & Carey, 1990). First, content should be logically arranged and organized within the course, "The better the organization of the course site, the easier it will be for the participants. The less the participants have to worry about how to use the technology, the more likely they are to participate actively in the course" (Palloff & Pratt 1999, p. 103). Second, as with any course, traditional or online, it is essential the course has clearly stated learning objectives (ACE, 2002; Dasher-Alston & Patton, 1998). Third, assessment practices should be consistent with stated learning objectives (ACE, 2002). Fourth, learning activities should utilize the capabilities of the online environment; noting that the design may have to be adjusted from that of the traditional course to work effectively within the technology (Roblyer & Ekhaml, 2003). Fifth, courses need to be accessible by a wide variety of learners. Thus, as the American with Disabilities Act (1990) requires, courses must be accessible by students with special needs (Levy, 2003; Ommerborn, 1998). Finally, when working towards a successful distance learning program, it is important that all courses for the degree or certification are available online (WCET, 1999).

Course Management System

One of the findings in Green's report, Campus Computing 2002 , was that 82% of 632 institutions surveyed had standardized on a single course management system. This trend makes selecting the most appropriate system even more important. Some factors to consider in selecting a course management system for a distance learning program include ease of use, breadth of the tool set, and the consistency and visual appearance of the user interface.

The ease of use of the course management system is critical for faculty success. Morgan (2003) found faculty who decreased their use of a course management system attributed this decline to the fact that the course management system was time consuming, inflexible, and difficult to use. Ease of use is no less important to students. The ideal situation is to have a course management system that is easy to navigate and use, allowing faculty and students to focus on the content and not the technology (Palloff & Pratt, 1999).

The course management system should have a range of tools available that faculty need to manage their courses. This pre-packaging of tools allows the faculty to focus on teaching and not have to worry about programming or manipulating technology to achieve the desired results (Morgan, 2000).

The course management system should also allow the institution the opportunity to customize the interface so students experience a similar look and feel in each of their courses. This includes allowing institutions the ability to "brand" their courses and programs through standard navigation formats or other methods (Carnevale & Olsen, 2003). The course management system should also have the flexibility to create visually appealing course sites in order to create a greater interest on the part of the participants (Palloff & Pratt, 1999).

Technical Support

When discussing the technical support requirements of a quality distance learning program, there are two distinct aspects to consider: 1) the required infrastructure, including the course management system, and 2) the technical support required by the faculty and the students. While the need to provide both types of support may seem obvious, many institutions begin to offer distance learning courses without sufficient planning as to the technical and support requirements such an initiative will demand (Broskoske & Harvey, 2000).

Many distance learning programs began with a small cadre of faculty members, without consideration for the technical demands the growth of such endeavor would place on the infrastructure (Katz, 2003). Therefore, when assessing an institution's current situation or planning for a new implementation, one must make sure that the technical infrastructure is robust and scalable enough to handle the initial and continuing demands placed upon it (ACE, 2002; Chiti & Karlen, 2001). A related aspect to providing the necessary infrastructure, is allocating enough resources, including staffing and funding, to administer the course management system. This financial commitment is necessary to achieve a quality program (ACE, 2002; Morgan, 2000).

The other side to technical support moves the focus away from servers and bandwidth to training and service. It is necessary to provide technical training to the faculty (WCET, 1999; Morgan, 2000) and the students (Morgan, 2000; Osika & Sharp, 2002) using the system, as well as providing staff who are available to help resolve technical problems for faculty and students (Carlson et al., 1998; Morgan, 2000; Palloff & Pratt, 1999). Faculty and students will have technical support needs. Proper planning can facilitate prompt resolution and enhance the success of the program.

Program Support

While the focus to this point has centered on what is necessary to support a quality distance learning program in the actual classroom, there are many programmatic issues that must be addressed if the program, as a whole, is to be successful (Broskoske & Harvey, 2000; Chiti & Karlen, 2001; Levy, 2003). Programmatic issues are those that build the foundation for success across the institution and help provide the support students and faculty need outside of the actual classroom. Programmatic issues outlined in this model are separated into four distinct areas: 1) instructional support, 2) student support, 3) policy and procedural issues, and 4) executive support.

Instructional Support

Broskoske and Harvey (2000) summarized the need for instructional support by stating, "more sophisticated hardware and software may provide greater capabilities for the distance learning program, but the potential advantages will not be realized if additional competent staff support and advanced faculty training are not provided at the same time" (p. 39). For distance learning to flourish, faculty need to be supported in their professional development and in the development of course materials.

Training programs that introduce faculty to the challenges of teaching online and assist them in effectively adapting their courses to an online environment is the foundation of instructional support (Carnevale & Olsen, 2003; Chiti & Karlen, 2001; Dasher-Alston & Patton, 1998; Wagner, 2000; WCET, 1999). However, simply providing training is not sufficient. Instructional support staff need to be available to work individually with faculty to address the specific needs of their courses and students. Having the ability to collaborate with instructional designers and media specialists will allow faculty, who are first content experts, to move their materials online in a manner that is most conducive to learning (Chiti & Karlen, 2001; Morgan, 2000; Weston & Barker, 2001).

In addition to providing instructional support staff, institutions that excel in distance learning provide instructional support systems for the faculty members themselves. Such systems include recognizing the time it takes to create online courses by rewarding this effort. It may also include providing mechanisms for peer assistance and mentoring to occur between faculty involved in distance learning (Morgan, 2003; Schauer, Rockwell, Fritz, & Marx, 1998). As faculty are typically the first ones involved when a course is created or offered, it is essential that their efforts are adequately supported by the institution.

Student Support

Once distance learning begins to expand and students in larger numbers are participating, the institution must look at offering a full range of student support services geared to the online learner. Levy (2003) stated that "one problem with online distance learning planning is that too much focus is on instruction and not on student services" (p. 6). Without a systematic plan for supplying the support necessary to meet the needs of online students, the students are very likely to delay completion of the program or drop out entirely (Rumble, 2000). This suggests that institutions should offer online access to the critical services enjoyed by traditional students, such as orientation, registration, fee payment, advising, and access to libraries and research resources.

An important service for student success is the availability and/or requirement of an orientation to distance learning (ACE, 2002; Broskoske & Harvey, 2000; Levy, 2003; Palloff & Pratt, 1999; Spitzer, 2000). This orientation should provide insights into the rigors of learning online, the skills and behaviors successful students possess, strategies for functioning within the online environment, and identification of the support systems provided by the institution (Palloff & Pratt, 1999). Other student support systems should include online registration (Belanger & Jordan, 2000; Chiti & Karlen, 2001), online payment for courses (Belanger & Jordan, 2000; Carnevale & Olsen, 2003), online advising (Rumble, 2000), and access to a full range of online library and research resources (Chiti & Karlen, 2001; WCET, 1999). Only through careful planning and provisioning of student support systems can an institution expect to achieve a quality distance learning program.

Policies and Procedures

Institutions wanting to achieve and sustain a quality distance learning program must implement policies and procedures that support and clarify how distance learning will be administered. This includes providing guidance on how to maneuver through governmental regulations, such as copyright laws and the American with Disabilities Act. More importantly, the ability to sustain a quality distance learning program will depend on the policies established at the home institution.

According to several authors, the most important policy that an institution can implement is one which places teaching in an online environment as something meaningful for tenure and promotion (ACE, 2002; Carlson et al., 1998; Chiti & Karlen, 2001; Olcott, 1996). The institution also needs to establish a clear policy on intellectual property (Broskoske & Harvey, 2000; Chiti & Karlen, 2001). Without a clear understanding of ownership, the institution and faculty will eventually conflict. Regardless of the stance on ownership, it is best that the issue be resolved and publicized before courses are created.

Administratively, policies and procedures need to be implemented to provide a recurring budget sufficient to cover the costs of supporting all aspects of distance learning (Carr, 2001; Chiti & Karlen, 2001; WCET, 1999). More often than not, institutions begin offering distance courses without understanding what it will cost to maintain the program (Morgan, 2000). If adequate time is not spent upfront identifying the costs necessary to offer a distance learning program and the revenue streams needed to support such costs, an instructionally solid program may fail due to lack of financial stability.

Executive Support

While the role of faculty and students is apparent, administrators often do not see how important they are in influencing the overall effectiveness and quality of the distance learning program (Levy, 2003). Executive leadership at the institution needs to provide clear commitment to the distance learning program. This commitment can be shown by including distance learning initiatives in the mission, vision, and strategic plan of the institution. When a distance learning program is initiated, the institution's strategic plan should clearly outline the expected benefits and return on investment the program is intended to generate (Belanger & Jordan, 2000).

Clear commitment from the executive leadership will also allow a common vision to be shared across the institution. The leadership of the institution must guarantee the entire organization understands and shares the same vision of success by addressing the question of "Why do we want to do this" (Carlson et al., 1998)? A quality distance learning program depends on the entire institution providing support to the initiative. This support can only be garnered if everyone understands why and what they need to do to participate.

Community Support

In order to sustain a quality program, an institution needs the support and acceptance of the larger community. The most vital aspect is to have the program accredited by the institution's accreditation body. Without proper accreditation from a nationally recognized body, the program's success will be limited regardless of its quality (Carlson et al., 1998; Chiti & Karlen, 2001; WCET, 1999). Once accredited, the institution needs to guarantee the program will provide students the skills and knowledge necessary to be recruited and placed into jobs. The recruitment of students into positions will impact the marketing of the program and the general public's impression of the online degree or certificate (Broskoske & Harvey, 2000). The perception of the program will also influence the overall perception of the quality of the institution (Broskoske & Harvey, 2000). Therefore, adequate planning and implementation of online support systems can help strengthen the institution's distance learning program making it an asset and not a burden on the reputation of the hosting institution.

Through the literature, 47 elements necessary to support a quality distance learning program were identified. The next question is to determine if these are indeed critical to successfully support a quality distance learning program.

Validating the Identified Elements

The methodology determined to best fit the question of validating the elements was the Delphi process (Linstone & Turoff, 1975). The Delphi process is defined by Delbecq et al. (as cited by Murray & Hammons, 1995) as "a method for the systematic solicitation and collection of [expert] judgments on a particular topic through a set of carefully designed sequential questionnaires interspersed with summarized information and feedback of opinion derived from earlier responses" (p. 423).

The design of the Delphi process for this study included three rounds of data exchange between panel members. Three rounds were incorporated into the design of the Delphi process in order to allow any items added by the panel members in round one to have at least two iterations of data exchange. This decision was based on Mitchell's (1991) finding that most changes in Delphi responses occur in the first two rounds.

Each round was administered via the Internet through online questionnaires. At the completion of each round, the results were summarized and comments compiled. Each panel member received information on the mean, median, interquartile range (IQR), and compiled comments for each element to use as feedback when completing the subsequent round of the study.

During the initial round, an additional element, marketing of the program, was suggested by a panel member, supported by the literature, and included into the subsequent rounds for evaluation by the panel. This brought the final number of elements evaluated to 48.

Panel Selection

To obtain valid and reliable results in any research study, the involvement of the appropriate participants is critical. This becomes even more critical with a Delphi design, as the conclusions are based solely on the experts' knowledge and experience (Clayton, 1997; Fleming & Monda-Amaya, 2001; Mitchell, 1991). The convened panel of 23 experts was located primarily across the United States , with one member located in Germany and another in Great Britain . Sixteen of the participants (70%) were female. The primary job function of 10 participants (43%) was director of his/her institution's teaching and learning center, distance education center, or similar department. The other job function included faculty member (n = 5 or 22%), technology support or administration (n = 3 or 13%), instructional designer (n = 2 or 9%), distance learning consultant (n = 2 or 9%), and a teaching and learning account executive (n = 1 or 4%). The 23 participants averaged 8.5 years of experience with distance learning, ranging from 4 to 27 years.

Criteria for Accepting an Element as Valid

The primary purpose of this process was to validate that the elements contained in the model are essential to support a quality distance learning program. Validity, in terms of this study, is defined by the panel members reaching consensus that an element is critical in the support of a distance learning program. Although, this definition presents two questions: 1) How does one define consensus? 2) Where on a seven point rating scale does the split between critical and non-critical items occur?

Consensus in this study was defined as an element with an IQR and standard deviation less than or equal to two. These criteria for consensus reflected not only the dispersion of the panel members' responses but also the variation in their numeric values. If an element met the criteria for consensus, the data was then assessed to determine if it met the established level for criticality, which was established as an element having a median rating of at least a four on a seven point rating scale.

Realizing the setting of criteria in a Delphi study is a somewhat arbitrary process (Murray, 1995; Fleming & Monda-Amaya, 2001; Kreber, 2002), the criteria set for this study errs on the side of inclusion to best align with the purpose of the study. As this study is to provide distance learning administrators guidelines as to what types of support systems are needed, the decision was made to potentially include elements that may not be critical, as opposed to erroneously omit elements that may be essential.

Analysis of Elements

Using these criteria, 44 of 48 elements met the established criteria for consensus and all of these elements had a median value greater than four. Therefore, these 44 elements were retained in the Concentric Support Model. The IQR, standard deviation, median, and mean for these 44 elements are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1: Elements Meeting the Criteria for Inclusion and their Respective Data

Element |

IQR |

Std Dev |

Median Rating |

Mean Rating |

• Faculty are technically competent |

2 |

1.23 |

5 |

4.83 |

• Faculty are knowledgeable about online pedagogy |

1.5 |

1.80 |

7 |

5.83 |

• Technology is easily accessible by faculty |

1.5 |

1.46 |

6 |

5.87 |

• The faculty are motivated to teach online |

1 |

0.85 |

6 |

6.22 |

• Technology is easily accessible by students |

1 |

1.70 |

7 |

6.09 |

• Students are motivated to learn online |

1.5 |

1.55 |

7 |

5.96 |

• Courses allow for interaction between students |

0 |

1.59 |

7 |

6.39 |

• Content is logically arranged within the course |

2 |

1.14 |

6 |

5.74 |

• Courses allow for interaction between faculty and students |

0 |

1.27 |

7 |

6.65 |

• Courses have clearly stated learning objectives |

0.5 |

1.08 |

7 |

6.43 |

• Assessment practices are consistent with stated learning objectives |

1 |

0.95 |

7 |

6.48 |

• Courses actively engage the learner |

0.5 |

0.71 |

7 |

6.65 |

• Courses are ADA compliant |

2 |

1.97 |

6 |

5.77 |

• All courses necessary for the degree are available online |

2 |

1.93 |

6 |

4.91 |

• Faculty find the CMS easy to use |

0 |

1.40 |

6 |

5.70 |

• The CMS has a broad tool set |

1.5 |

1.61 |

5 |

5.04 |

• Students find the CMS easy to use |

1.5 |

1.61 |

6 |

5.83 |

• The CMS provides a consistent user interface for students across their courses |

1 |

1.34 |

5 |

5.17 |

• The CMS creates or allows for a visually appealing user interface |

2 |

1.86 |

5 |

4.45 |

• The institution has the technical infrastructure to support DL |

0 |

0.83 |

7 |

6.65 |

• IT has sufficient resources allocated to the administration of the CMS |

0.5 |

1.43 |

7 |

6.35 |

• Technical training is available to faculty |

1 |

1.58 |

6 |

5.87 |

• Technical support is available to faculty for the resolution of technical problems |

0 |

0.42 |

7 |

6.78 |

• Technical training is available to students |

2 |

1.70 |

6 |

5.22 |

• Technical support is available to students for the resolution of technical problems |

1 |

0.49 |

7 |

6.65 |

• Assistance is available to faculty in developing content for their courses |

1 |

1.52 |

6 |

6.14 |

• Instructional support staff is available to work individually with faculty |

1.5 |

1.10 |

6 |

5.87 |

• Training is available to faculty regarding online pedagogy |

1 |

1.26 |

7 |

6.30 |

• Faculty are able to receive release time for the development of online courses |

1.5 |

1.37 |

5 |

4.83 |

• The institution provides avenues for peer assistance and/or mentoring |

1 |

1.34 |

6 |

5.35 |

• An orientation to DL is available and/or required of students |

2 |

1.39 |

6 |

5.87 |

• Students have access to online advising |

1.75 |

2.00 |

6 |

5.68 |

• Students have access to library and research resources online |

0.5 |

1.38 |

7 |

6.43 |

• The institution provides faculty assistance in adhering to copyright policies |

1.5 |

1.56 |

6 |

5.83 |

• Teaching online is seen as a worthwhile endeavor in the tenure |

1 |

0.83 |

7 |

6.35 |

• The institution has a clear policy on intellectual property |

1 |

1.48 |

7 |

6.22 |

• There is a recurring budget allocated to cover the costs of supporting DL |

0.5 |

0.56 |

7 |

6.70 |

• There is a clear commitment from the executive leadership from the executive leadership of the institution |

1 |

1.39 |

7 |

6.13 |

• A common vision of the purpose of DL is shared across the institution |

1.5 |

1.33 |

6 |

5.70 |

• DL is included within the institution's strategic plan |

1 |

1.52 |

7 |

6.04 |

• Graduates of the online degree are recruited and/or placed into jobs |

2 |

1.62 |

6 |

5.39 |

• The online degree is accredited by a recognized agency |

1 |

1.65 |

7 |

6.22 |

• The general public has a positive impression of the online degree |

2 |

1.14 |

6 |

5.87 |

• The program is marketed to the appropriate audience. |

1 |

0.86 |

6 |

6.26 |

Four elements failed to meet the established criteria because their IQR exceeded the maximum of two. These elements and their respective data are displayed in Table 2.

Table 2: Elements Not Meeting the Criteria for Inclusion

Element |

IQR |

Std Dev |

Median |

Mean |

Students are technically competent |

2.5 |

1.7 |

5 |

4.6 |

Learning activities within the course utilize the capabilities of an online environment |

2.5 |

1.27 |

5 |

5.48 |

Online registration is an option for students |

3 |

1.91 |

6 |

5.26 |

Online payment for courses is an option for students |

3 |

2.07 |

6 |

5 |

Given the importance of technical competence of students in the literature, the comments of the panel members were reviewed for this element. Based on the comments provided by the panel members, there was strong agreement that students needed to have basic technical skills, such as "turn on a computer, deal with email, use a browser, and do word processing." However, the term technically competent seemed to indicate a skill level beyond what was critical for success. One panel member summarized this by her statement, "With the L[earning] M[anagement] S[ystems] available, [the students] do not have to be too sophisticated. Think about it." Therefore, the statement was reworded to, "Students have basic technical skills" and retained within the model.

The second element, "learning activities within the course utilize the capabilities of an online environment," was interpreted one of two ways by the panel members. One interpretation can be summarized by a panel member's comment, "If the class is online, it's using the capabilities of the online environment." The other focused on the need to utilize online tools only when aligned with the instructional objectives as reflected in the following comment: "While the tools within the platform exist, there also isn't a point in using technology for the sake of technology. Reasoned use is the most important factor." This lack of consensus within the group eliminated the element from being included in the model.

Online registration and payment were the two other elements that did not meet the criteria for inclusion into the model and were removed. The panel members had varying opinions of whether online services were critical to the success of a distance learning program or only a convenience to the students. Reflecting on the composition of the panel, there were no students or student services personnel. If the panel had included members from these groups the result may have been different; thus, giving reason to replicate the study with another panel of experts which includes a more inclusive representation of roles and experiences related to distance learning.

The 46 elements that were validated by the panel are listed in Table 3 and displayed in the Concentric Support Model in Figure 2. The Concentric Support Model, introduced here, is provided as a tool for institutions to use in the planning and evaluation of their distance learning programs.

Table 3: Categories and Elements Contained within the Concentric Support Model

Faculty Issues • Faculty are technically competent• Faculty are knowledgeable about online pedagogy• Technology is easily accessible by faculty• The faculty are motivated to teach online

|

Figure 2: Concentric Support Model